|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Editorial On going viral

By Toh Hsien Min

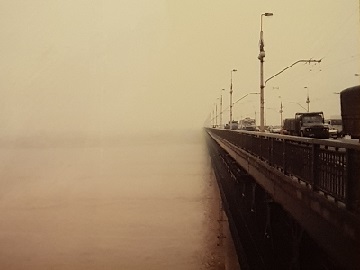

I've been to Wuhan. Relax. It was over two decades ago, and I was backpacking my way through China. I had arrived in the morning from one of those crushing 40-hour hard-sleeper slow trains from Xi'an, and had most of a day to kill before catching a slow boat down the Yangtse River to Shanghai. Wuhan isn't the most intuitive travel destination, and it left not very much of an impression compared to the cities that bookended it. In the days of film cameras and having to ration film cartridges, I didn't take enough photographs to refresh my recollection of the place. My only vivid memory is of the Wuhan Changjiang Bridge; crossing it on foot from Wuchang, the Hanyang side seemed so far away as to be a bit of a haze. I think I then made the considerably less fussy crossing to Hankou, just to be able to say I had been to all three of Wuhan's constituent cities. I have a faint impression of dinner at a roadside restaurant and ordering a dish of what was allegedly chicken covered with chillis, although that could well have been a fragment dislodged from Xi'an, before circling back to the passenger port to board the boat under the glare of painfully white fluorescent lights. Editorial self-correction Feb 2020: Dragging out my 1997 travel journal, I realise I've remembered everything wrong. I got off the train at Hankou after a 22-hour journey, which meant I crossed the rivers counter-clockwise rather than clockwise and spent the least time on Wuchang – which is the hazy bit below. And dinner was at a decent-looking seafood restaurant.  In modern-day China, Wuhan serves as a hub for central China. Its universities attract students from all over China, and consequently its tech startup scene is one of the most vibrant in the country. It has a dry noodle tradition for breakfast, and a crayfish obsession for supper. The Hubei Provincial Museum contains some of the most prized archaeological artefacts for the country, such as a complete set of Bianzhong bells that date several millennia. But all of this might as well be for nought now. The WHO guidelines for naming new infectious diseases advise that disease names should not include geographic locations, but one suspects such considerations will have come too late for Wuhan. Now when you type Wuhan into Google, you have to scroll a long way down before you get to the city. The attention on the Wuhan virus, oddly enough, makes me think of the work of Daniel Kahneman in behavioural psychology, and specifically what he would call WYSIATI ("What You See Is All There Is") - that the human brain operates an associative machinery that foregrounds activated ideas such that anything outside of that might as well not exist. In this case, the activated idea comes from the frequency format of the information presented, which is the natural recourse of news articles, as opposed to the probabilistic format. Told of a given number of deaths arising from the Wuhan virus, the mind cannot help but focus on the highly emotive prospect of death. (In similar vein, insurance often uses - deliberately or otherwise - this cognitive over-focus to sell products, as in the well-known case of "terrorism cover".) The substituting question that the mind delivers to us often leads to our providing the wrong answers, so that we end up taking actions that are entirely placebo in nature or, worse, counter-productive. For example, all evidence to date does not support the case of contracting the Wuhan virus simply by breathing in air (excepting the pathological case of someone infected sneezing directly into your nasal passages), which is why the government advisory is to wear masks only if you have flu-like symptoms. Otherwise, wearing a mask is unlikely to increase your protection against the virus even as it uses up resources that may be put to better use. While it is good to take precautions, for me there is also the question of whether the actions we take are in fact helping the situation. So meanwhile I am actually enjoying running counter to consensus, in that as I head out to lunch in the malls around my workplace I am observing the restaurants being much emptier than usual. I don't have to fight for a seat in the foodcourt at Changi Airport's Jewel, for example. Everyone being paranoid is giving me a free pass - with people avoiding the airport, this is exactly where I won't catch 2019-nCoV. Anyway, if you've locked yourself in and are in need of diversion, this quarter's issue of QLRS might just do the trick. The poetry has excluded all Chinese nationals from Hubei, and has alighted, purely from a coincidence on the quality of the writing (and one unanswered email from a non-Singaporean), upon an all-Singaporean lineup. Elsewhere, there is quite a focus on grief, arising from Shu Hoong's article on Nick Cave and our interview with Linda Collins. There are other themes - the pieces I have personally contributed on criticism, or perhaps more accurately because of an extended discussion on criticism, are with luck only a taster for the next issue, where (we're hoping) some of this will come even further into the foreground. If Kahneman is right, then perhaps what we put forward can have some influence in shaping the directions that Singapore literature take. QLRS Vol. 19 No. 1 Jan 2020_____

|

|

|||||||||||||

Copyright © 2001-2026 The Authors

Privacy Policy | Terms of Use |

E-mail