|

|

|

|

Proust Questionnaire: 17 questions with Shirley Geok-lin Lim

By Yeow Kai Chai

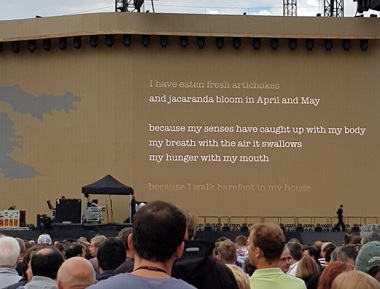

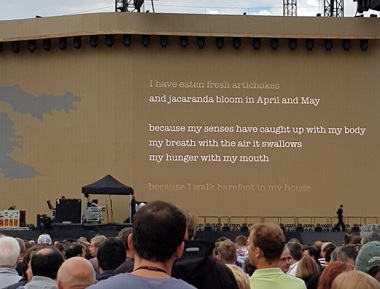

There is a poem by Shirley Geok-lin Lim which has been beamed in stadia globally, projected onto gigantic screens, alongside verse by Walt Whitman, Naomi Shahib Nye and Lawrence Ferlinghetti, to millions of U2 fans during the Irish band's Joshua Tree tour in 2017 and 2019.  That poem is 'Learning to Love America', from the collection What the Fortune Teller Didn't Say (West End Press, 1988), which has become a clarion call post-Sept 11, performed frequently by other speakers, and most recently, adapted into a libretto for music score in 2019. One line stands out: "because countries are in our blood and we bleed them." For Lim, that line rings especially true. Born in Malacca, she is now an acclaimed Asian-American writer and scholar of poetry, fiction, creative non-fiction and criticism, and her impressive bibliography, ranging from postcolonial and Southeast Asian writing to 20th century American literature, underscores a fluid, transnational vision. Her first collection of poems, Crossing The Peninsula (Heinemann, 1980), clinched the Commonwealth Poetry Prize, a first both for an Asian and a woman. She has published ten poetry collections and three verse chapbooks; three books of short stories; two novels; a children's novel; and The Shirley Lim Collection. Her 1996 memoir, Among the White Moon Faces, which is a frank account of her upbringing in colonised Malaysia and the making of an Asian-American woman, received the American Book Award. As a scholar, she has edited/co-edited numerous volumes and journals including Reading the Literatures of Asian America (Temple University Press, 1992); Approaches to Kingston's The Woman Warrior (Modern Language Press, 1991); Power, Race and Gender in Academe (MLA Press, 2000); The Forbidden Stitch: An Asian American Women's Anthology (Calyx, 1989); Writing Singapore (National University of Singapore (NUS) Press, 2009). Currently Professor Emerita and Research Professor of English at University of California, Santa Barbara, she has taught widely in the United States as well as overseas, including as Chair Professor of English in Hong Kong University and stints at Massachusetts Institute of Technology; NUS; National Institute of Education at Nanyang Technological University; National Sun Yat-Sen University in Kaohsiung, Taiwan; and City University of Hong Kong. 1. What are you reading right now?

I've been reading for a chapter on ethical eating. My concerns in that thought piece are not settled simply because the chapter is drafted, and I am still reading the relevant books, articles, and scientific papers appearing on the Internet daily. 2. If you were a famous literary character in a novel, play or poem, what would you be and why?

I would be Jane Eyre, because I identify with her miserable childhood and the abusive education system she survived, and because I would re-write her life. Instead of "Reader, I married him," I would say, "Reader, I rejected him." Charlotte Bronte imagined Jane as a young girl who yearned for freedom from restrictions of poverty and social constraints. She (both Charlotte and Jane) dreamed of travelling beyond known horizons, and found some of that freedom that helped alleviate their wretched childhoods through art. In marrying blind Rochester ("Master"!), Jane remained in Thornwood environs and sacrificed her painterly talents to serve as his eyes. MY Ms Eyre would have used her share of her uncle's inheritance to live in France, making her contribution to European art, which even then had a few women painters of some note. I will, of course, be re-writing fiction as "faction." 3. What is the greatest misconception about you?

That I am a coherent subject. The pandemic lockdown confirms that, although not bipolar or schizophrenic, I am a reclusive who enjoys sociability. I have a strong life force and self-harming ideations, and am a comic depressive (or perhaps a depressed funny bone). I am altogether ambivalent, think in continuous ambiguities. People take me as a rational writer and academic, but I am an incoherent human. 4. Name one living writer and one dead writer you most identify with, and tell us why.

I most identify with Maxine Hong Kingston, or more precisely, I would most like to be a writer like Maxine. She is a wordsmith genius, principled, kind, generous, warm, modest, and her books are works of art. For a writer who has passed, I identify with Doris Lessing, whose first novel, The Grass is Singing, had a huge impact on me. The narrative itself is powerful, but what I reverberated to is her style. Her long writing life covered multiple genres. She was not interested in exploiting her growing fame, and published under a pseudonym, Jane Somers, to be sure publishers and readers were responding to the work and not to the author's reputation. Both Hong Kingston and Lessing express political positions, but their writings escape the nets of "nationality, language, religion" through the flight of creativity that James Joyce advocated. 5. Do you believe in writer's block? If so, how do you overcome it?

I do not have writer's block, but only self-evasive strategies more commonly known as procrastination. I do suffer from author's block, the inability to let go of a manuscript for publication. My anxiety has all to do with authorial remorse, the fear of publishing work that is not perfect, that is weak. For the last two years or more, I have been waiting to submit three new poetry collections. 6. What qualities do you most admire in a writer?

Inventiveness. All can be forgiven if the writer has invention: on-going, unceasing originality that changes the sphere in which it has its life. It's what Wallace Stevens was gesturing to in his 'Notes Towards a Supreme Fiction,' inventive imagination creating out of nothing a wonderful something. Hence the power of Apple's mantra, "Imagine," which resides as we all know now in "I." 7. What is one trait you most deplore in writing or writers?

Such a difficult question. There are so many deplorables in the writing circuitódishonesty, fake-ness, et cetera. As I age, I try to give up being judgemental. But at the core of what discomforts me most in writing is shallowness. Sometimes playing in the shallows is cool; but shallow writing damages young minds (elders have been exposed to so much that either they have been toughened against it or such damage by now is irremediable). The young are particularly open to learning how not to fear, to enjoy and to grow deep feelings and thoughts. Wading in shallow water is fun, but being able to swim can save lives. Deep writing does not preclude easy reading. Children's literature, mythology, and fairy tales, like many novels, are easy yet incredibly gripping reads, and they haunt the child reader for life. 8. Can you recite your favourite line from a literary work or a piece of advice from a writer?

My first mantra is Samuel Beckett's "Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again Fail again. Fail better." The second is attributed to Picasso and repeated by Steve Jobs, "Good artists copy. Great artists steal." These explain my writing process, which is interminable revision ("Fail better!"), and how my books develop. Joss and Gold steals from/is structured on Puccini's opera, Madama Butterfly; and my second novel, Sister Swing, steals some of its plot lines from Mozart's The Magic Flute. 9. Complete this sentence: Few people know this, but I...

. . . am extremely loyal to good friends. However, like Mr Darcy in Pride and Prejudice, my flaw is a temper perhaps too resentful. "My good opinion once lost is lost forever." Friends who betray once are never trusted again. 10. At the movies, if you have to pick a comedy, a tragedy or an action thriller to watch, which would you go for?

I only watch comedies or "happy" movies (The Two Popes, for example). There is so much tragic in my past experiences that I will not shed tears in a movie, and my stress level is so elevated that action thrillers come too close to stroke-suspense! 11. What is your favourite word, and what is your least favourite one?

My favourite word is "Yes," and my least favourite "No." Or is it the other way around? 12. Compose a rhyming couplet that includes the following three items: insurrection, Jonker Walk, heirloom.

My House Has Two Exits

(With thanks to Han Suyin's My House Has Two Doors)

Balik kampung after US insurrection,

to Jonker Walk heirloom jual murah election. 13. What object is indispensable to you when you write?

Paper, and pen or pencil. I've written on napkins, edges of newspapers, facial tissues, any available papery object, when struck by the fire to scribble an image, a line, a few end rhymes. 14. What is the best time of the day for writing?

Early morning, 7 am onwards. 15. If you have a last supper, which three literary figures, real or fictional, would you invite to the soiree, and why?

The question stumps me. The Biblical gathering brought 12 to dine with one for whom it was the last supper. Why limit MY last supper to three literary figures? I would fill the rented hall with many such: Buddha, Ee Tiang Hong, Cecile Parrish, W.E.B. DuBois, Nelson Mandela, Doris Lessing, J.V. Cunningham, Florence Howe, Tillie Olsen, and so many more who'd lit the way forward for me. I name only those who have passed. The living would over-run your word count. 16. Boey Kim Cheng says in a 2014 essay on you: "Her own hybrid nature, the entangled strands of her make-up, Peranakan, Chinese, Malaysian, Asian-American, with multiple attachments to places like Singapore and Hong Kong, and her own migration, preclude any real homecoming." In the wake of recent socio-political upheavals, and the fallout from the coronavirus pandemic including restrictions on global travel, what does home mean to you these days?

What clarified for me during the pandemic lockdown is that home means Earth, that blue, shimmering, vulnerable sphere in the matrix of dark matter. No Mars or Venus can be home for an earthling like me, nor can I cherish only one country, one city, one place. My California backyard yielding weeds and imperfect fruit and vegetables, Hong Kong alleys redolent of compressed history, Singapore's Little India and Kuala Lumpur's Brickfields, Malacca's Cheng Hoon Teng Temple, Parisian avenues, Portuguese tiled-wall train-stations, Adelaide's vineyards, Newcastle beaches in New South Wales: I've made a home wherever I have walked, between water and land, sidewalks and strangers' houses. What is home to a flaneur who absorbs the world through her senses? The Earth belongs to all of us, and for a walker, that home is freehold. 17. What would you write on your own tombstone?

We come from Light and return to Light.

QLRS Vol. 20 No. 3 Jul 2021

_____

|

|

|

|

|